Earlier this year, Light in the Attic Records released a 22-song album called Creation Never Sleeps, Creation Never Dies: The Willie Dunn Anthology. Compiled by Grammy-nominated producer and artist Kevin Howes over eight years, the anthology includes I Pity the Country, The Ballad of Crowfoot and Charlie, songs that convey the message of the devastation caused by colonialism and the Canadian residential school system.

The anthology honors Dunn’s powerful music and unique talent, recognizing him as a trailblazer who was ahead of his time throughout his career. Dunn passed away in 2013, and he’s finally beginning to receive some of the recognition he deserves after actively creating music throughout his life.

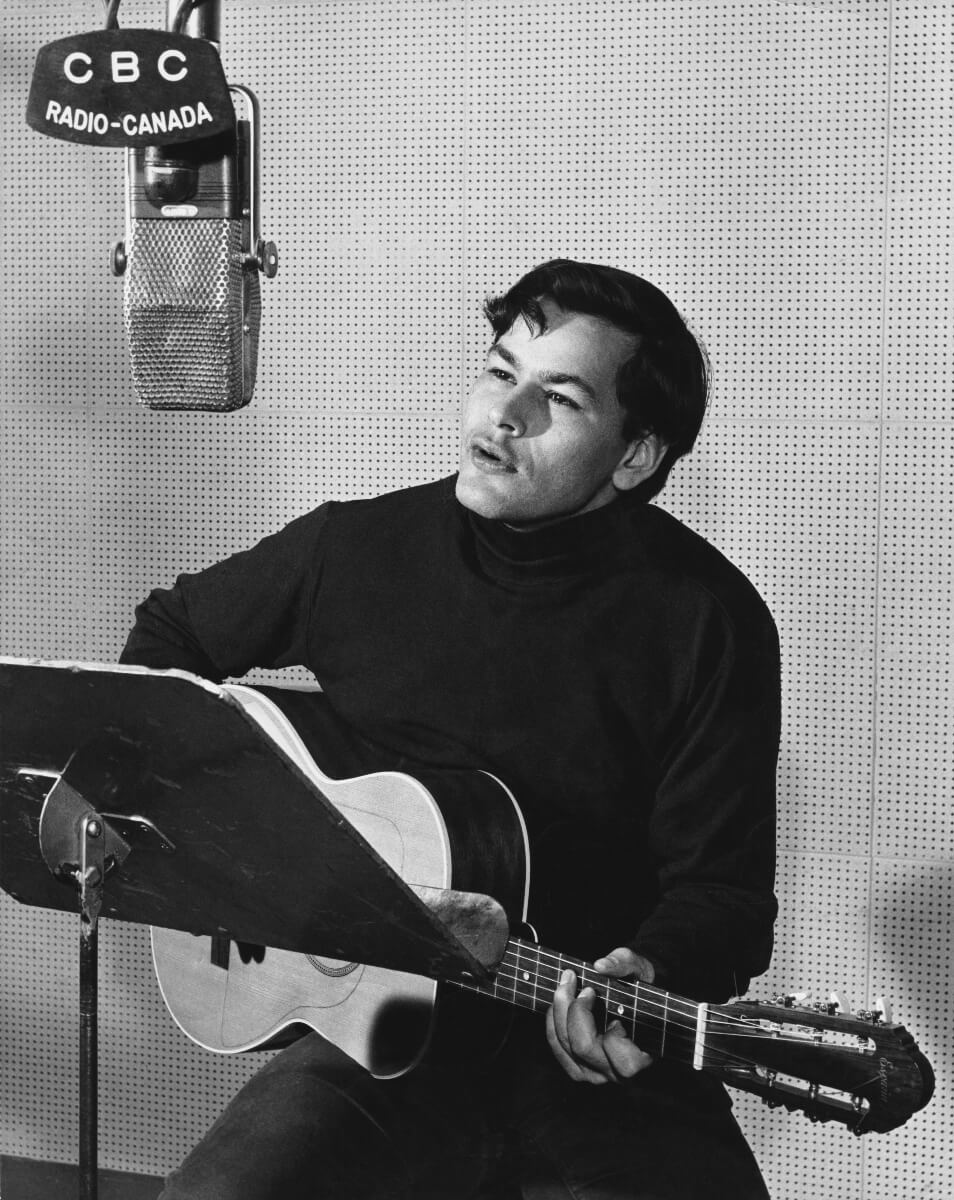

Willie Dunn Began His Career in the 1960s in Montreal

Born in 1941 in Montreal, Dunn’s ancestry was Mi’kmaq and Scottish. He released several albums over his career, the first being Willie Dunn released in 1971, but he began his music career during the 1960s when he started performing in coffeehouses across Montreal.

In addition to being a musician, Dunn was part of the National Film Board’s (NFB) first all-Indigenous production unit. Although he gained some traction with the CBC and through the creation of what is often called the country’s first music video, The Ballad of Crowfoot, in 1968, he never saw the career success he deserved while he was alive. Today, people are finally beginning to acknowledge the horrors of the residential school system and the level of damage caused by deeply rooted systemic racism and prejudice, but during the 1960s, ‘70s and beyond, most of the country was generally unwilling to listen to the messages Dunn was spreading.

Now, with the anthology that was released in March, younger generations are being exposed to Dunn’s work, which is sadly still just as relevant as it was decades ago. The themes of his music are particularly poignant this year, as the remains of hundreds of Indigenous school children from former residential schools in British Columbia were uncovered earlier this summer. This is the first year the government has designated September 30th, which is also Orange Shirt Day, as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, an opportunity for Canadians to understand the legacy of residential schools.

Willie Dunn’s Song “Charlie” Tells the Story of Chanie Wenjack

One of Dunn’s songs, Charlie, which is part of the anthology, tells the tragic story of Chanie Wenjack — a 12-year-old Ojibwa boy who died of starvation after running away from Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora in 1966. Chanie was trying to escape the school to be reunited with his father who lived 600 km away.

“He’s a-gettin’ mighty hungry

It’s been a time since last he’s ate

And as the night grows colder

He wonders of his fate

For his legs are wracked with pain

As he staggers through the night

As he sees through his troubled eyes

His hands are turning white”

In addition to inspiring Dunn’s song in 1972, the story has since led to several other creations by Indigenous artists. This includes the painting Little Charlie Wenjack’s Escape from Residential School by Anishinaabe artist Roy Kakegamic (2008) and works by filmmaker Terril Calder. Other artists including A Tribe Called Red and Gord Downie have also created art stemming from Chanie’s story, following Dunn’s lead.

Related Articles

Willie Dunn’s Music Was His Strongest Vehicle for Political Activism

Prior to learning to sing and play guitar, Dunn spent three years in the Canadian army, earning a UN Congo Medal from his time serving in Africa. Later in his life, he entered the world of politics. In the federal election of 1993, he won the New Democratic Party’s federal nomination for Ottawa-Vanier, finishing in fourth place.

Music was still his strongest vehicle for political activism, and he used it throughout his life as a platform to speak out against injustices against Indigenous communities in Canada. Released in 1968 Dunn, the short film The Ballad of Crowfoot tells the story of the Siksika (Blackfoot) chief who negotiated Treaty 7 for the Blackfoot Confederacy in the 19th Century. The film was directed by Dunn and uses his music along with archival photos.

The Ballad of Crowfoot

The film was the NFB’s first to be directed and filmed entirely by Indigenous people. It hauntingly conveys the horrors inflicted by colonial settlers, while simultaneously hinting at a ray of hope for a better future.

“Well, the buffalo are slaughtered, there is nothing to eat

The government’s late again with the meat

And your people are riddled with the white man’s disease

And in the summer they’re sick and in the winter they freeze and

Sometimes you wonder why you signed that day

But they broke the treaties themselves anyway

And it’s eighteen hundred eighty-nine

And your death star explodes and then it falls

Crowfoot, Crowfoot, why the tears?

You’ve been a brave man for many years

Why the sadness? Why the sorrow?

Maybe there’ll be a better tomorrow”

Dunn Recognized as a Canadian Trailblazer in Film and Music

Dunn was inducted into Edmonton’s Aboriginal Walk of Honour for his achievements in 2005, and was honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Indigenous Music Awards. The Prism Prize also honoured his legacy with the creation of the Willie Dunn Award, which recognizes Canadian trailblazers in film and music.

Creation Never Sleeps, Creation Never Dies: The Willie Dunn Anthology features an overview of Dunn’s life and career, lyrics, discography and filmography, previously unreleased recordings, photos and interviews and much more. It can be purchased at lightintheattic.net.

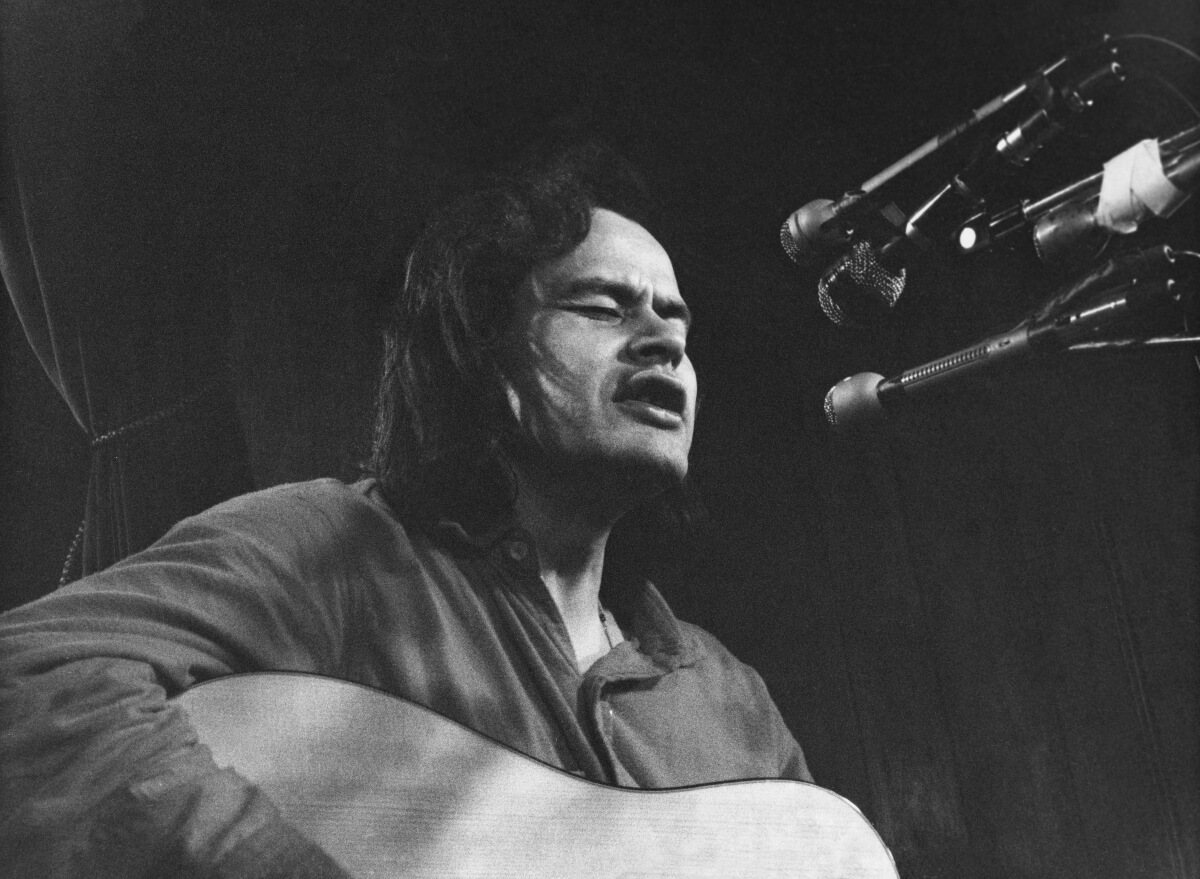

Lead image: A still from Alanis Obomsawin’s 1976 Amisk film. Photo courtesy of NFB.